A Dictionary of the Yoruba Language, Oxford University Press, London, Ibadan, 8th impression, 1962

A Dictionary of the Yorùbá Language, University Press PLC, Ibadan, 2002

This

is the most widespread Yorùbá dictionary, several reprints by different

publishers exist. You can get the old versions very cheap in

second-hand bookstores. It is a reprint from a dictionary published by

the Church Missionary Society Bookshop of Lagos in 1913. Today it is

still printed (in Malaysia) by University Press Ibadan and sold for a

very affordable price in Nigeria, I have seen it in University

bookshops. Guess what the original publishers’ opinion was on

traditional Yorùbá religion?The book is divided equally into two sections, English-Yorùbá and Yorùbá-English. There is no section on grammar, tones or tenses, just one page on how to pronounce the vowels and certain letters. You open up the book and it starts with the letter A, great after Abraham, here I have the feeling that I am dealing with a real dictionary. Although the book is so old, it has a good layout design and a nice typography. Yorùbá words are indexed in bold letters, a hanging indent gives a clear structure, you quickly find what you are searching for. Its size is very handy, it fits into a pocket and is not heavy at all. But...

Forget about the tone marks in this book, they are not at all according to the modern Yorùbá standard. E.g. when we look at the word òrìṣà, which usually is written and spoken with three low tones (low-low-low). Here it is written òriṣa (low-mid-mid) with the given meaning: an object of worship, idol. We quickly look up the other expression I want to compare in all the dictionaries, orò, here gets translated as bullroarer, bull-whizzer. So there’s no word on the Orisha, but instead the Orisha’s sounding instrument is mentioned (which would correctly be called iṣẹ́ Orò). As an Orisha is only an object of worship according to this dictionary it makes sense mentioning only the bullroarer involved in his cult. Èṣu, here with low-mid tone, is translated as we expect it to be done by the Church Missionary Society, as devil, Satan, demon, fiend. The word aróbọ̀, written here as àróbọ̀ is translated as prevarication or artful way of dealing one with another, what is already another description than doing business as a middleman.

The book includes vowels which have a tilde, a small grapheme that looks like a wave, above them. This is used for gliding sounds, but I am not sure in what way exactly, because a tilde goes up, down and up again. Does ã now mean áaà, àá, áà, àa or aá? I have no idea. Also some words like ayé, meaning world, are written aiyé. The ai is an old form of spelling that is not in use anymore today as it makes no difference in pronunciation.

The book was always very useful to me in my Yorùbá classes. I used to work with old copies of educational books and books about Yorùbá culture, most of them published in the 1960s in Nigeria for (primary) school. Beautiful books, by the way, with great artwork and illustrations. Their authors might have had exactly this dictionary as a resource. Although compiled from a Christian perspective this dictionary has many adjectives, verbs and nouns that are connected to the traditional Yorùbá way of life and culture. For someone like me, who is interested in 'deep Yorùbá' like Ifá verses, this is interesting. Many words I think are hardly in use anymore or understood by e.g. a young and modern Yorùbá from Lagos. Imagine a dictionary written in your mother tongue in 1913, for me this would be the language my great-grandfather has spoken. An example Titilayo Oyinbo once mentioned, with this dictionary you might get into dialogues like this one with young Yorùbá people: 'Ẹ jọ̀ọ́, ṣí fèrèsé!' – 'Á-a! Kíni itúmọ̀ fèrèsé?' – 'Window'!

I also bought the newer version of this book from the University Press of Ibadan published in 2002, you can see the new cover above on the image. The Amazon advertising text says this version has been 'revised and enlarged considerably'. I thought they would at least have corrected the tone-marks, but I was disappointed. It is a re-print from the original book, same layout, nothing has changed. Òriṣa (low-mid-mid) still is an idol, no word for computer or internet was added. I own the version from 2002, I am not sure if there is a newer version already available, I guess not. So here Yorùbá in Nigeria stays on the standard from 1913.

Kayode J. Fakinlede: Yoruba. Modern Practical Dictionary. Yoruba-English. English-Yoruba. Hippocrene Books, Inc. New York, 2003. Fourth printing 2011.

As far as I know this is the latest Yorùbá dictionary that was published. Fakinlede also published a very good Beginner's Yorùbá course that I reviewed in my blog post on Yorùbá courses. This dictionary is recommended by language schools, as it was to me in New York by the Yorùbá Cultural Institute. It is heavy in weight and has impressive 700 pages - because it lacks a good dictionary layout. It is too heavy for carrying it around a lot. It is printed in huge letters as one list and additionally lots of space on the pages around the text stays blank (see the picture above where I compare three pages of dictionaries), the paper is also heavy for a dictionary. A good graphic designer versed in typography could reduce it by half I guess and make it a really cool and handy book. By the way, talking about typography: this book has an issue a Yorùbá dictionary really should not have. The author, or the graphic designer, used a font, a typeface, which does not feature dotted vowels. I see this often when people try to write in Yorùbá on their home computer. What your computer program likely does, without asking you, is following: dotted vowels are simply replaced in another font (most likely Arial Unicode). You can see it in the image below, this happened to all the letters ọ, ẹ and ṣ. You can see that they do not fit into the chosen typeface. The spacing is different, one word looks like divided into two parts, or letters appear too bold or too light-weight. In this case a classical Book Antiqua font gets combined with letters from a font called Sans Serif, in typography this is like mixing oil and water.

All dotted vowels are written in a Sans Serif font, the rest is a Book Antiqua.

But

let’s get to the content. The spelling of tone marks is correct and up

to date, this is the modern standard of today. We look up the three

chosen magic words. Browsing through the book, printed in large size

with a good index, we quickly find the first explanation: Òrìṣà, any Yoruba deity.

The word is written with a capital O, as I prefer to write it, good

point, shows respect for the traditional believers. Òrìṣà Orò, on the

other hand, is not mentioned at all, just the other similar word orò, meaning festival, habit.

Strange, excluding a cult that is still very much alive in many Yorùbá

towns and the author for sure was cross-checking with the older Yorùbá

dictionaries that all mention Orò. If I am learning Yorùbá the

traditional cultural expressions should be included, I believe. We

browse to Èṣù, again capital E: devil; bad influence.

It seems like it will take some more time until the dictionaries won’t

mention Èṣù as Satan any longer. This mistranslation by Crowther for his

Yorùbá bible is not easy to get out of the heads of the people. Maybe

we should introduce Yemọja for the Virgin Mary? Fakinlede writes àróbọ̀ with tone-marks like in the dictionary from the Christ Missionary Society, but translates it in the words of Abraham, as doing business as a middleman.

The foreword mentions the author of this book in his profession as a research scientist. The preface tells us about the first-time inclusion of complex scientific and mathematical terms into a Yorùbá dictionary. This book has translations like: plasmalemma, iwọ̀ọ pádi; odontectomy, ehin yíyọkúrò; lymphatic system, ètò iṣọ̀n omi-ara; macrocephaly, orí nlá; intumescent, wíwú; Fahrenheit, ìdíwọ̀n ìgbónáa ti Farín-áiti; protozoan, ẹranko onípádíkan, etc. I am really curious who is using these expressions. The international language of science is English, and its terminology is based on Latin and Greek words. Even here in German speaking countries, if you want to do research, there’s only one language that counts. What’s the use of inventing artificial Yorùbá termini, that translate diseases like macrocephaly as 'big head‘? It is a description of a symptom, but not the term macrocephaly and its medical discourse. At the same time the dictionary is lacking traditional terms like Òrìṣà Orò. Is the dictionary intended for medical doctors, who can now tell their malaria patients that they have ẹranko onípádíkan in their veins? Is there scientific research in Nigeria, and if yes, (why) is it done in Yorùbá language? Is it part of a political movement to get rid of the colonizer’s language? From the perspective of someone interested into Yorùbá culture, not Yorùbá medical or mathematical science, this dictionary could be improved.

But Fakinlede's book is the only good contemporary modern standard Yorùbá dictionary available on the market today, as far as I know. All the older ones you can only find in second-hand bookshops or directly in Nigeria. I am also using Fakinlede a lot at home, usually it is the first choice when I am looking up some common contemporary verbs, nouns or daily expressions. It has the correct spelling and tone-marks, but it is not perfect.

The foreword mentions the author of this book in his profession as a research scientist. The preface tells us about the first-time inclusion of complex scientific and mathematical terms into a Yorùbá dictionary. This book has translations like: plasmalemma, iwọ̀ọ pádi; odontectomy, ehin yíyọkúrò; lymphatic system, ètò iṣọ̀n omi-ara; macrocephaly, orí nlá; intumescent, wíwú; Fahrenheit, ìdíwọ̀n ìgbónáa ti Farín-áiti; protozoan, ẹranko onípádíkan, etc. I am really curious who is using these expressions. The international language of science is English, and its terminology is based on Latin and Greek words. Even here in German speaking countries, if you want to do research, there’s only one language that counts. What’s the use of inventing artificial Yorùbá termini, that translate diseases like macrocephaly as 'big head‘? It is a description of a symptom, but not the term macrocephaly and its medical discourse. At the same time the dictionary is lacking traditional terms like Òrìṣà Orò. Is the dictionary intended for medical doctors, who can now tell their malaria patients that they have ẹranko onípádíkan in their veins? Is there scientific research in Nigeria, and if yes, (why) is it done in Yorùbá language? Is it part of a political movement to get rid of the colonizer’s language? From the perspective of someone interested into Yorùbá culture, not Yorùbá medical or mathematical science, this dictionary could be improved.

But Fakinlede's book is the only good contemporary modern standard Yorùbá dictionary available on the market today, as far as I know. All the older ones you can only find in second-hand bookshops or directly in Nigeria. I am also using Fakinlede a lot at home, usually it is the first choice when I am looking up some common contemporary verbs, nouns or daily expressions. It has the correct spelling and tone-marks, but it is not perfect.

Ọlabiyi Babalọla Yai: Yoruba-English, English-Yoruba Concise Dictionary, Hippocrene Books, New York, 1996.

Another Yorùbá book from the publishing house Hippocrene books, but this time the dotted vowels are printed in the same font as the rest of the publication. The graphic design could be improved. The handy book is made for travelers, it fits really into every small pocket. Most words are very briefly translated into one single word, this saves a lot of space. Yorùbá words come with an 'English pronunciation' in brackets, guess this is intended for people who do not speak Yorùbá at all. This information is useless in my opinion, as the tonemarks are still missing in this 'English version' and it does not even come close to the original Yorùbá, e.g. Òṣùmarè comes with the information (oshoomanray). I have doubts that Yorùbá people would understand me, asking around for Orisha Oshoomanray. Especially if it is really urgent and you are looking for the (shalaoonga) you might have a problem. Everyone who has this dictionary in his or her pocket knows how to pronounce Yorùbá, all the tonemarks are written in this book. Yai translates Orìṣà, Òrìṣànlá, Òòṣàálá (oreesha, oreeshaoonla, o-oshaala) as primordial deity, god of creation, obviously mixing up Ọbàtálá’s oríkì with the general word òrìṣà. He also writes orìṣà (mid-low-low), maybe this is a spelling mistake and not intended. Èṣù he lists in two variants, as Èṣu (low-mid) and Èṣù (low-low) translating it as (ayshoo) messenger god. Òrìṣà Orò is not mentioned and àróbọ̀ (arobaw) is translated as middleman business and petty trade, bringing together Crowther’s and Abraham’s translations and the tones (low-high-low) from the Church Missionary Society. It is a handy book, good for travels.

Chief/Ms FAMA Àìná Adéwalé-Somadhi: FAMA’s Èdè Awo Òrìṣà Yorùbá Dictionary (Revised and Expanded Edition), Ilé Ọ̀rúnmìlà Communications, San Bernardino, CA, 1996, 2nd publication 2001.

This book is exactly what the title says, in this sense it can be recommended for this purpose. It has only one section, Yorùbá into English, not the other way round. But this is what it is intended to be: giving the Yorùbá student, or the Òrìṣà/Ifá student a book to work with and a basic orientation. It has translations for lots of oríkì, priest’s titles, all the 256 Odù and many verbs and expressions that have to do with Òrìṣà worship. It includes also a basic Yorùbá vocabulary, like numerals, common verbs, adjectives, etc., but the main focus is on Òrìṣà termini. It includes some re-translations from Lukumí, Cuban expressions, into proper Yorùbá or makes it clear where the difference lies, e.g. in the term àdìmú.The layout and the index is good, you quickly find the words you are looking for, the font type is featuring dotted vowels, not like Fakinlede above. A cheap adhesive binding will lead to many lose pages soon. This is not good for a dictionary, which will be opened and closed thousands of time. I would wish for a hardcover version, thread-stitched, more expensive but durable, and a cheap light-weight paperback edition.

The definitions of the three magic words are: Òrìṣà, n. some of the Irúnmọlẹ̀ that distinguished themselves while on earth. They include Gods like Èṣù, Ọ̀rúnmìlà, Ọ̀ṣun, Ṣàngó, Ògún, Ọbàtálá etc. Nice one. Orò, an Òrìṣà. Short, but correct. Ẹ̀ṣù, God of justice. ~alájé money drawing Ẹ̀ṣù; ~aṣẹ́ta spell repellent Ẹ̀ṣù […] She continues with various types of Ẹ̀ṣù. First time Satan or the devil are not mentioned here. Of course, we are expecting this book to be written from the perspective of a traditional believer, and she clearly is aware of this discourse.

The word àróbọ̀ is translated by Chief FAMA as going back and forth asking for discount. This adds to the translation as prevarication or artful way of dealing one with another and doing business as a middleman. Combining all of these translation from four dictionaries I have the feeling that finally now I can understand what àróbọ̀ means and how it is used. So this example shows that as a Yorùbá student it is good to have all these dictionaries on your side. Translation varies, looking up word consumes lots of time. I hope that one day someone will sum up all these books and finally publish a good Yorùbá dictionary, that is contemporary but not forgetting about the traditional cultural expressions.

L.O.Adéwọlé: A bilingualized Dictionary of Yorùbá Monosyllabic Words, The Research in Yorùbá Language and Literature Department, Ọbáfẹ́mi Awólọwọ̀ University, Elyon Publishers, Ilé-Ifẹ̀, Second Edition 2014.

I bought this book visiting the University bookshop in Ilé-Ifẹ̀. Printed and bound in a very low quality. It will hardly be available outside of the country. I cannot compare any of my chosen words from this book, as it is only on monosyllabic words. This dictionary is a very useful resource for the Yorùbá language student, because every entry comes with lots of examples and there is a section Yorùbá-English and one on English-Yorùbá. Let’s see the entry for the word gbá (i) to fry: Ó gbá epo náà ‘He fried the red palm oil’ (ii) to kick: Ó gbá bọ́ọ̀lù ‘He kicked the ball’ (iii) to sweep: Ó gbá ilẹ̀ ‘He swept the floor’ (iv) to slap: Ó gbá mi létí ‘He slapped my ears’ (v) to run after: Ó gbá tì mí ‘He ran after me’ (vi) hit: Ó gbá mi lábàrá ‘He hit me with his hand’ (vii) smite: Àwọn orúnkún rẹ̀ n gbá ara wọn ‘His knees smote together’ (viii) struck: Ó gbá mi lágbọ̀n ‘He struck me on the chin’ (ix) box: Ó gbá mi létí ‘He boxed my ears’. Nice, isn’t it?The font used is something like Arial Unicode, there are no problems with the dotted vowels. The dictionary lacks an alphabetical page-index but it is easy to read and you can find the words you are looking for, highlighted in bold letters, quickly. With all these examples how to practically use the words it is a good source to study and very recommended. I am not sure if this work is based on the book by Chief Isaac O. Delanọ from 1969, also published by the Institute of African Studies on the University of Ilé-Ifẹ̀ and entitled 'A dictionary of Yoruba monosyllabic words'. The publisher printed a phone number on the book cover. In case you want to order, try Naija nomba 08034019061.

It can also be downloaded online as a pdf from the University of Ilé-Ifẹ̀’s website, but only with a huge problem: the pdf lacks all the dotted vowels. It was converted into another font type, obviously one that does not feature dotted vowels, and so all this information the author painstakingly provided just got lost. Maybe this was done on purpose not to ruin the income made by selling the correct version printed in the book. Anyhow, if you want to download it for free, there is a website link below.

Link

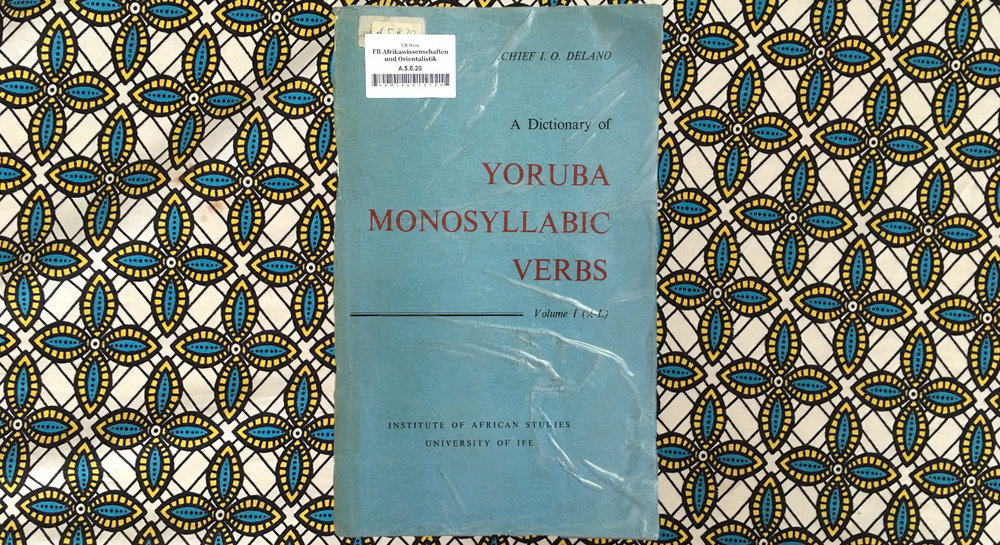

Chief I.O. Delano: A Dictionary of Yoruba Monosyllabic Verbs, Volume I (A-L), Institute of African Studies, University of Ife, 1969.

After having read the book above from L.O.Adéwọlé I wanted to compare it with this one. There’s a huge difference, Delano’s version is very extensive. Published in 1969 its pages are written on a typewriter. It is about monosyllabic verbs only, no nouns or adjectives are included in this list. Every verb comes with its various meanings, a complete sentence in Yorùbá shows how it is used and a translation of the sentence into English is added. Delano also lists verbs based on monosyllabic word roots. E.g. dí leads to verbs like díbọ̀, díbọ́n, dídágìrì, dífá, dáfá, dígbà, dígbèsè, dìjà and many others, I cannot list them all here, but it seems to be very complete. Gbẹ́ e.g. has the meaning 1. carved: Gbẹ́nàgbẹ́nà gbẹ́ ẹ, the wood-carver carved it. 2. Cackled: Adiẹ na gbẹ́, the hen cackled. It follows a list of verbs like gbẹ́bẹ̀ (gbọ́ ẹ̀bẹ̀), Baba gbẹ́bẹ̀ ọmọ rẹ, the father listened to his child’s entreaties; Ọlọpa London ki igbẹ́bẹ̀, London police do not listen to begging (once he arrests someone), followed by a list of about 50 more gbẹ́-verbs with examples! It has no English-Yorùbá section but it is a great resource for intense Yorùbá studies. I would love to have a modern version of this book! A hidden gem.

Chief M.A.Fabunmi: Yoruba Idioms. Pilgrim Books, 1970/African Universities Press, Ibadan, 1984 (Reprint).

This is a great book that consists of a collection of Yorùbá idiomatic expressions, edited by Wande Abimbola. Phrases are deciphered, explained in Yorùbá, translated into English and an example is included. E.g. Gba omi mu – Ó tọ́ láti ronú púpọ̀ nipa; o gba wàhálà. Deserves much thought, consideration and energy. Ọ̀rọ̀ obìnrin yìí gba omi mu tí a ba fẹ́ ṣe ìrànlọ́wọ́ fún un. Or another entry: Le ìdí mọ́ - Dojú ìjà kọ; kí á fẹ́ bá ẹni tí ó kéré sí wa jà. To face in a fight. Ẹni tí a lè mú ni à á lèdí mọ́. Great resource. A very rare book that can improve your poetic and advanced Yorùbá skills a lot!

Thomas Jefferson Bowen: Grammar and Dictionary of the Yoruba Language. With an Introductory Description of the Country and People of Yoruba. Smithsonian Institution, 1858.

I mention here two more very old dictionaries, just because they are so easy to access and historically interesting. Thomas Jefferson Bowen was an American Southern Baptist missionary and arrived in Nigeria in 1850 to settle down in Ijaye. As an expert for 'black nation missions' he had also spent some months before in Brazil, preaching the gospel. Bowen established three Baptist missions in Nigeria and then returned back to the United States where he published several books on his experiences in Nigeria, like this grammar and dictionary book.The four-word-comparison: Orisa is translated simply as an idol, Èsu is the devil and Satan. Oro is the god of civil government, the executive of the state deified, well done, good and short description speaking of Orò’s political power. Arobọ is translated as petty traffic.

Google digitalized the original publication of Thomas Jefferson Bowen, it can be accessed online, more than one version Is available.

Link

Rev. Samuel Crowther: A vocabulary of the Yoruba language. Together with the introductory remarks by the Rev.O.E.Vidal, Seeleys, London, 1852.

Samuel Ajayi Crowther was a freed Yorùbá slave from the region around Ọ̀yọ́. Around the age of 12 he was loaded onto a Portuguese slave ship that was eventually stopped by the British and forced to unload in Freetown, Sierra Leone. There is a big Creole Yorùbá community there up to today. He was educated by the Church Missionary Society, did groundbreaking work translating the bible into Yorùbá language and later returned to Nigeria as a missionary.This original first list of his vocabulary, later published as a dictionary by the Church Missionary Society (see the review above), translates oriṣa still as deity, objects of worship; gods, idols! The two termini deity and gods were not printed in the dictionary sixty years later anymore. Èṣu is the devil, Orisha Orò is not mentioned at all and arobọ̀ is translated as petty trade. See how it all started, writing Yorùbá in Roman letters, using the Western alphabet, follow the link to one of the Google digital book scans.

Link

Michka Sachnine, Akin Akinyemi: Dictionnaire yorùbá-français suivi d’un index français-yorùbá. Éditions Karthala et Ifra, Paris, 1997.

This hardcover-book has an alphabetical index on top of the page and is produced in a good quality, thread-bound, easy to read, good layout. I call this one a real book. As the subtitle says it has a Yorùbá-French and a smaller French-Yorùbá section. Nothing to complain about, I am sure it is very useful as Yorùbá is also spoken in the francophone Benin Republic. I guess there are many people interested in this Yorùbá-dictionary. Looking up my four words I came across òrìṣà ~ òòṣà, n. terme désignant toutes les divinités du pantheon yorùbá, à l’exeption du Dieu créateur. The description is alright for me, the greek term “pantheon” applied to an African cultural expression is another story, it quickly sketches an image in your mind that is not adequate, but for a brief explanation I also would not know of a better term. Èṣù, n. dieu messager: il aurait enseigné l’art de la divination à Ifá et aurait conclu un pacte avec lui; en consequence, c’est lui que transformet les sacrifices au Dieu supreme. Il est ambigu et provocateur. Il a souvent été assimilé au décepteur des contes. Il a aussi été assimilé au diable par les chrétiens. Very good description, speaking of Èṣù as messenger and working closely with Ifá, bringing sacrifices to God, and being assimilated with the devil by the Christians. Orò is the dieu justicier lié au culte de la terre, se manifestant par l’emploi d’un rhombe: il ne doit en aucun cas être vu pa les femmes, sous peine de mort. Rhombe utilize par le dieu. Coutume, rite. Also a good and short description of Òrìṣà Orò, god of justice, feared by women, the bullroarer. Indexed here together with the same word orò for custom, habit, in one dictionary entry. Usually in the other dictionaries orò is mentioned twice, once as Òrìṣà, once as habit. The authors here decided to group the two words, which are actually the same but have very different meanings, together. Àróbọ̀ is not listed in this dictionary.

Abeni Adeola: Yoruba Language. The Yoruba Phrasebook and Dictionary.

This book has no publisher, but it says it is printed by Amazon in Poland. So I think it is a self-published book. It looks like a MS-Word document, has a table with two columns throughout the whole book, left side English, right side Yorùbá. Or better write it Yoruba, without diacritic marks. Except for some numerals there are absolutely no tone-marks throughout the whole phrase book and its so-called mini-dictionary. I consider it useless, except for native speakers, and I guess they do not need a phrase-book for 'Is it wireless internet?' or 'I am here for a business meeting.' The book was just published a few weeks ago. I can imagine maybe this is a production problem, maybe the author wrote it with tone-marks, but due to some technical self-publishing conversion issues it cannot be printed in this type-face, so it lacks all the tone-marks. It could be a nice small booklet with some highly contemporary Yorùbá phrases. I would love to ask for wireless internet in Yorùbá language when checking in at some Hotel in Naija, this sounds fun! The book has even conversation starters and useful phrases you won’t find in any other book like 'Mo fẹran nigba to ba ṣe eyi.' Please, Abeni Adeola, add tone-marks! Then it could be recommended to Yorùbá students.

Kasahorow: Yoruba Learner’s Dictionary. Yoruba-English English Yoruba.

Same as above, printed by Amazon in Poland, a self-published book I guess, delivered within two days. With a really bold approach. It starts with an introduction on the Yorùbá language, it mentions letters, spelling conventions, sounds and gives an interesting general guideline on Writing Modern Yoruba, I quote here: Do not use accents of top of vowels (diacritics). Instead structure your sentence to avoid ambiguity. For example, write Sọ Yoruba lojo ojumọ (Box A is bigger than box B) instead of Sọ Yòrùbá lójo ojúmọ́. The version without diacritics is easier to write and just as clear and unambiguous. Aha. What…? Really? An interesting new point. But not only that the word Yorùbá is spelled wrong in the only sentence in this book featuring diacritic marks, I also do not know what the sentence in brackets means, the one with the boxes. Needless to say that the whole book (a dictionary!) comes without diacritic marks, which leads to entries like gba collect, gba accept or ogun battle, ogun inheritance, ogun August, ogun twenty. I would say that is not perfect for a book entitled Yoruba Learner’s Dictionary, this could be improved… Sorry ooo!

Lydia Cabrera: Anagó Vocabulario Lucumi (El Yoruba que se habla en Cuba), Prologo de Roger Bastide, Colección del Chiherekú, Ediciones Universal, Miami, Florida, 2007

This is not a dictionary, but a collection of phrases of Lukumí vocabulary, the remains of the Yorùbá language from times of slavery on the island Cuba. Cabrera collected these words in the 1950s, they are still in use today in rituals for the Orisha, especially in songs, prayers and incantations. I have written an extensive article on this topic in the blog, see the entry The Yorùbá guide to Lukumí for details. I mention it here because this is an English language blog on Orisha related themes, and I know everyone reading this post who is learning Yorùbá comes across the Cuban version of Orisha worship. I looked up my four magic words in this book.Orisha or Oricha, English and Spanish versions are used alternatingly, is not listed as a single word, just in various word-combinations and phrases. There’s no translation for it into Spanish language. As this dictionary consists of words used only by Olorisha there is no need in translating the word, probably as santo, saint, how Orisha are called in Cuban Spanish (saints, not gods). Oro is listed as un orisha. Ocha que se llama con matraca y pilón, y que suena como el Ekue de los ñañigos. Viene cuando se llama el Egu (a los muertos) en una ceremonia donde no puede haber mujeres ni muchachos. In English this means Oro is an Orisha, called by a rattle (seems like Cabrera did not know about the bullroarer) and a mortar, that sounds like the Ekue of the ñañigos. Ekue seems to be a sounding instrument I have never heard of, the ñañigos are another ethnic group in Cuba related to the Efik from the Calabar region of Nigeria. He comes when the Egu are called, probably this should read Eégún in Yorùbá, because in the brackets it says 'the dead ones', in a ceremony where neither women nor young men are allowed. Eshu is listed as diablo, devil, el hermano de Elegua, the brother of Ẹlẹ́gbáa, de la misma familia, of the same family. Cubans think of Èṣù and Ẹlẹ́gbáa as being two different type of energies of the same Òrìṣà, a separation that does not exist like this in Nigeria. Èṣù is the wild energy outside, hardly controllable, while Ẹlẹ́gbáa is closer to the human world. Also San Antonio Abad is mentioned, the Catholic Saint identified in the diaspora with the worship of this Orisha. This means that Èṣù, although called diabolic, is at the same time identified with a Catholic saint, what makes a huge difference to Nigeria I believe. Surprisingly we even find the word àróbọ̀, in its Lukumí version aroboni, meaning comerciante, in English dealer or trader, what would be equivalent in meaning to the trade mentioned in the other Yorùbá dictionaries. The added –ni is likely the verb 'to be' in Yorùbá, this means 'it is trade', but the sentence is used like a noun for a profession of someone. This happens very often in Lukumí, more or less there is still a certain feeling for the meaning of a word, but let’s call it a very poetic way of using the ancestor’s heritage from the cruel times of slavery.

Mario Michelena y Rubén Marrero: Diccionario de Términos Yoruba. Pronunciación, sinonimias y uso práctico del idioma lucumí de la nación Yoruba. Prana, Mexico, Miami, Buenos Aires, 2010.

Although called “diccionario” this is far away from being a dictionary, and very far from the language Yorùbá! The authors, a studied technical engineer and a professor of accounting, dedicate their life to anthropological studies. They explain in the prologue that this book is about Lukumí phrases, brought to Cuba "by the Yoruba and Congo slaves from Nigeria". It is an interesting book, because the authors obviously have no knowledge about the Yorùbá tonal language, yet they use this term in the title of their book. They made up their own grammar based on what is called Lukumí in Cuba, the remains of Yorùbá language, used in songs and prayers to the Orisha and not spoken as a language anymore today. Three different tone levels or open and closed vowels are not mentioned at all. It is funny to read from the Yorùbá perspective, especially their pronunciation rules or tenses. Let’s take a look e.g. on the Yorùbá word ẹbọ, meaning sacrifice, offering. They translate it written as e-bbó in Spanish as limpieza or English as cleaning and the pronunciation rule tells us to call it el-bó. They also have another version, ebbó, translated as offering. In general they have all kind of words pronounced with a letter "l" in between, like Olbatalá, Ololdumare, Olggún, Elelguá. I know Spanish a lo Cubano is very nasal, but by inserting an “l” this is definitely too much emphasized. There are rules like whenever certain words end with -ilé, -kué and -dupe there has to be an ‘o’ added, like in ‘mo-dupé’, which is pronounced ‘moldupueo’. In reality the “o” or “òòò” frequently added to all kind of Yorùbá phrases is just to emphasize what one is saying. Another rule tells us that the prefix yiolo is added to a verb to form the imperfect tense: fó becomes yiolofó, ni becomes yioloni. Hmm..? Good morning means okuó-yireo and good afternoon becomes okuó-yi mao. Even the Orisha names get “translated”, Ọbàtálá, whose Yorùbá name means literally king of white cloth is here the King who shines in greatness, Yemọja, the mother whose children are the fishes, is the mother of the seven depths (profundidades), Olókun, the owner of the sea becomes the compassion of the sea. There is a small list of “vocabulary” in this booklet, but I could find just one of my four words. The word Oro is translated as sacred, saint, blessed, venerable, consecrate, profane, help, mass, hymns, voice, tune, couplet, intonation. Orisha Orò is not listed, not even as Oru, as he is frequently called in Cuba.But this book is interesting for the passionate Yorùbá-Lukumí re-translation community. First there are the Improperios lucumi (Lukumí terms of abuse), which are new to me. Usually the discussions focus on the “sacred” language for the Orisha. Here the authors include everyday expressions like Eres un descarado! Yo me acosté con tu madre! Eres un idiota! translated into Lukumí. The other interesting part is the Lukumí version of the Christian Padrenuestro, The Lord’s Prayer, and the Avemaria. First time a Lukumí prayer can be directly compared to a written Yorùbá source! This raised many questions for me, as the daily bread is translated in this Cuban version as native Yorùbá food akara in Lukumí, while in the Yorùbá standard version from Nigeria it is oúnjẹ ọjọ́, the daily food. So I guess a Yorùbá slave translated it from Spanish or Latin on the island of Cuba. Or have Christians from Yorùbáland been among the slaves? Have free Yorùbá Christians travelled to Cuba later? Let’s close the book here. It is not a dictionary and not about Yorùbá language. From a linguistic view it is a completely crazy project, but I have to acknowledge that it brought up some very unconventional points to the Lukumí-Yorùbá discussion that have to be attributed to the authors. Yorùbá language students – just forget about this publication.

José Beniste: Dicionário Yorubá Português. Bertrand Brasil, 2011.

Judging a book by its cover I would immediately think the word “Yorubá” is spelled wrong here. It lacks a low-tone “u”. But after looking inside it is clear that the way the author writes “Yorubá” on the cover is obviously just the Portuguese version, maybe an adaption of the more often used “Iorubá”. All the Yorùbá words in this heavy, hardcover and thread-bound dictionary are correctly spelt with low, mid and high tones. A page index helps you to quickly find what you are looking for. The bold font for Yorùbá words, in capital letters only, is a bit eccentric, but makes it easy to read and the book has a professional design and is produced in a high quality, it will serve you for decades. Published in Brazilian Portuguese, most of the readers will probably be Olórìṣà, so I was curious about the translations for the words Òrìṣà, Orò, Èṣù and àróbọ̀.Òrìṣà is translated as Divinidades representadas pelas energias da natureza, forças que alimentam a vida na terra, agindo de forma intermediária entre Deus e as pessoas, de quem recebem uma forma de culto e oferendas. Possuem diversos nomes de acordo com a sua natureza. Mo ti gbogbo òrìṣà búra – Eu juro por todas as divinidades; Ẹ̀sìn òrìṣà ni mo nbọ - É a religião dos orixás que eu cultuo; Òrìṣà mi ni Ọ̀ṣun – Minha divinidade de devoção é Oxum. = òòṣà. A very complete dictionary entry describing the Òrìṣà as forces of nature, something you can hear very often especially in Brazil, and giving some sentences of examples. Orò is uma divinidade cujas ceremônias são feitas na floresta. O culto é proibido às mulheres, que podem ouvi-li, porém não podem vê-lo. O sacerdotes do culto é denominado de Abẹrẹ. Good and short description of Òrìṣà Orò, with a small additional information how Orò priests are called. The following entry is on the word orò, which has the same melody, but means ritual or tradition. Èṣù does not appear as the devil in this list, instead he is the Divinidade com diferentes atributos ligados à comunicaçao entre o céu e a Terra, aos caminhos e à fertilidade. Èṣù Ọ̀dàrà ló ní ìkóríta mẹ́ta – Exu faz uso da encruzilhada. In English this means Èṣù is a divinity with different attributes linked to communication between heaven and earth, roads and fertility. Finally even the term àróbọ̀ is mentioned as prevaricação, alguma forma de prejudicar alguém, in English prevarication, prejudicing someone. This book is highly recommended for the Brazilian Yorùbá students.

Eduardo Napleão: Vocabulário Yorùbá para entender a linguagem dos orixás. Pallas, 2011.

Published in the same year as the other Brazilian Yorùbá dictionary above, this one is a smaller and cheaper soft-cover book. As the subtitle says, it is designed to translate mainly terms for the community of Brazilian Olórìṣà. Translations are word-to-word, there are not many explanations or additional examples how the word is used. This saves a lot of space on the pages and weight carrying the book around. Only two of my four words can be found in this book. Òrìṣà is translated simply as Divinidade. Short, but we don’t expect a dictionary to give us an insight into the Yorùbá philosophy. The term orò is just mentioned as ritual, culto, liturgia, but not as Òrìṣà Orò. Although the Orò cult did not survive the middle passage to Brazil, I think it should have been mentioned in a dictionary for Olórìṣà, at least as Orò’s “twin brother” Egúngún is still being worshipped in Salvador da Bahia. Èṣù is Exu. Divinidade yorubana responsável pelo movimento, transporte, intercâmbio e comunicação. Guardião dos templos. Mensageiro dos orixás. Orixá responsável pelo policiamento da sociedade. One of the few entries with a long explication in this book. Èṣù as the deity of movement, transport, exchange and communication, guardian of the temples, messenger and responsible for policing the society. Èṣù is no Satan to the Brazilians. Àróbọ̀ is not mentioned. It is a handy book, light-weight and good for travels.

Fonseca Júnior, Eduardo: Dicionário antológico da cultura afro-brasileira : Português - Yorubá - Nagô - Angola - Gêge ; incluindo as ervas dos Orixás, doenças, usos e fitologia das ervas. São Paulo, Maltese, 1995.

The author of this book is professor of Political Sciences, Theology and Black Culture (according to his biography printed in the book) and works as a journalist. Forewords by the Brazilian Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Health, the Pan-American Organisation of Health, the Embassy of Nigeria in Brazil, the Academia Brasileira de Letras, the Sindicato dos Escritores do DF and the label of the Fundação Banco do Brasil on the cover make it clear: the author has done his homework. It is an impressive 670-page book that starts with chapters on slavery and continues with a description of the world of Orisha. He mentions all kinds of facts, from Abikú-children, so-called ministers of the Old Oyo empire, ranks and titles in Yorùbá society and the most important Orixás. An interesting timeline tells us about the Orixá-dynasty, called Sacred Kings of Oyó. This starts with Oduduwá, called Fundador da Cultura Afro (Founder of the Afro-Culture), 2000-1800 BC (yes, before Christ), mentions Xangô, Quarto Alafin de Oyó with 1500-1450 BC and Aganju, Sexto Alafin de Oyó around 1370-1290 BC. He also compares Oduduwá with the Egyptian Nimrod, Ogun with the volcano and Ishedale, daughter of Oba-Olokun, with Afrodite, so there’s a good mix of all the ideas about Yorùbá deities we have heard about within the last decades.First I thought this is a compilation like Lydia Cabrera’s book on the Cuban Lukumí terminology, a collection of words from Olorisha, used since the times of slavery. But instead the dictionary is a compilation of Portuguese words, that are translated into 'Yorubá', as the author writes it. For Yorubá he just uses a high-tone diacritic mark throughout the whole book, so he writes all words in mid and high tone, low tones don’t exist. But he also lists Yorubá or Nagô expressions, that are translated into Portuguese language, and includes Portuguese phrases that have to do with Orixá worship plus adds words from other ethnic influences, Indigenous-Brazilians, Ewe/Gbe (Gêge) and Bantu (Angola), all together in one alphabetical list. On the other hand he also seems to have included Yorùbá words from real Yorùbá dictionaries, e.g. he has one entry on Orixá, one on Ôrixá (with a circumflex on the first letter) and another one on Orisá (what he calls the original Yorùbá variant, no dotted s). I wanted to look up my four magic words: Orisá (Ôrixá) subs. em Yorubá: Anjo da guarda. etmo.: “Ori”=Cabeça; “Sá”=Guardiāo da Caça. Divinidade elementar da natureza. Figura central do culto afro. Ôrixá subs. afro-bras.: Personificação e divinização das forças da natureza, que bem pode ser traduzida por santo, na acepção católica. Orixá subs.corrupt. afro-bras. Anjo da guardia, Guardião da Cabeça. Divinidade elementar da natureza. etmo.: Orí=Cabeça e Xá=Guardião. Figura central dos cultos afro-brasileiros. Lit.=Anjo da guarda. Original em Yorubá: Orisá. Original em Gêge: Vodún. Original em Angola: Inkisse. Three different explanations on three different spellings of the word Òrìṣà. My second word, Èṣù, we find in its Portuguese version Exú: subs. em Yorubá: Esú. Divinidade Yorubana da fertilidade. Obs.: Erradamente comparado ao Diabo católico pelos colonizadores europeus, que precisavam destruir as culturas. Original em Angola: Mavambo. Original em Gêge: Legbá. É Orixá e mansageiro dos Orixás. So again he says the original Yorùbá word would be Esú. Just three letters and the author got all of them wrong. Èṣù, the god of fertility, interesting. This is a description you can read everywhere for art and ritual objects from Africa. If one does not know what it is about, it is the “god/symbol of fertility”, it is a term you could apply to almost all the Orisha. He also mentions that Èṣù is not the devil and that European colonizers intended to destroy the culture with this translation. Obviously in Brazil this is a discussed topic, maybe related to the Pentecostal groups which are fighting against the Olorisha since decades. The Yorùbá Èṣù is furthermore a synonym for the name of a god of the Angola people and the Ewe/Fon people, other ethnic groups that survived in Brazil from times of slavery, he also did that before with the term Òrìṣà. Fonseca mentions an Orisha called Orô, but obviously it is another entity than Orò in Yorùbáland. He writes Orô subs. em Yorubá: Uma qualidade de Oxalá, é muito cultuado em Ibadan, na Nigéria. È o dono do orí (cabeça) de um iniciado e a Ele á dedicado o topo do mundo, assim como o topo das cabeças de seus filhos. Recebe as mismas liturgias que Oxalá, porém com algumas variações mais profundas. Orô is a type of Ọbàtálá en Brazil. Àróbọ̀ or something equivalent (also in Portuguese translations) could not be found in this dictionary.

Just one last example that shows that this dictionary could be improved. The entry otá subs. em Yorubá: Inimigo, oponente, antagonista, adversário. Erradamente, é traduzido nos rituais afro-brasileiros como “pedra de assentamento de Orixá” (vide okutá). He translates otá as Yorùbá ọ̀tá (low-high), enemy. At the same time he says the Brazilian Olorisha got it wrong, because they call the stones consegrated to the Orisha otá, what is a mistake. But ọta (mid-mid) in Yorùbá really means stone! Time to close this book.

Have fun studying Yorùbá! If you know more dictionaries please let me know and write a small message! Ire òòò!

Comments